Frozen in Time: St. Ignace Winters Through the Ages

Winter in St. Ignace has always been about change—boats giving way to sleds, water turning to ice, people shifting with the season. These days, you can enjoy winter from the warmth of a local hotel, watching the Straits freeze over from behind a picture window. But before central heating and high-tech gear, surviving a Michigan winter took grit, resourcefulness, and a deep understanding of the land.

Anishinaabe Winters: Built for Survival

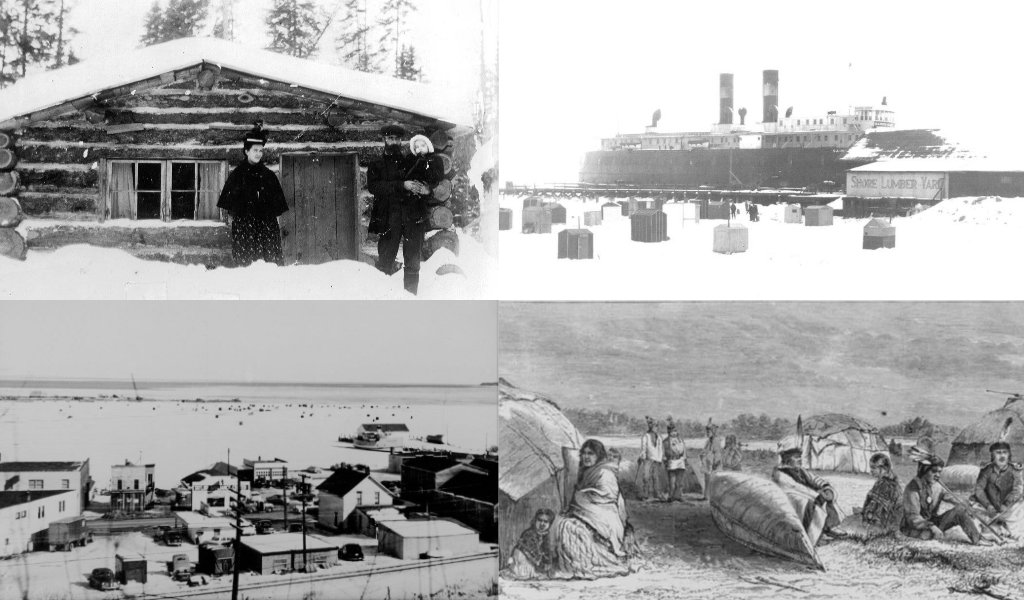

The Anishinaabe have called the Great Lakes home for generations, and their daily lives were shaped around the land, and the seasons. When winter rolled in, families gathered close to conserve resources and pass long nights with stories, songs, and traditions.

Their homes, called wigwams, were small but smart. They were made with wooden frames covered in bark, woven mats, and warm animal hides. In winter, moss and packed snow added even more insulation to preserve the heat from a central fire.

To ensure a steady food supply, the Anishinaabe stored smoked fish, dried meat, and wild rice in underground caches. During winter, ice fishing became an important source of food, and bone-tipped spears were used to catch the fish that lurked beneath the thick ice. Additionally, snowshoes made winter hunting possible by allowing hunters to track the deer and moose whose meat was dried and saved for months to come.

When the Straits froze over, the ice could be a benefit for travel. The Anishinaabe knew how to read the ice, spotting where it was safe to cross. With snowshoes on and sleds or toboggans — pulled by people or dogs — they’d carry supplies, firewood, and game across the frozen lakes.

Clothing had to be warm, yet flexible. Moose-hide coats blocked the wind, fur-lined moccasins kept feet warm, and deerskin leggings made it easier to move through deep snow. Snowshoe moccasins stopped them from sinking into snow drifts, and thick fur mittens kept fingers from freezing.

Winter was a season of stories, craftwork, and ceremonies. With the world frozen outside, families gathered around the fire to hear the legends that had been passed down for generations. Midwinter ceremonies marked the shift toward longer days, while hands stayed busy making clothing, tools, and anything else they’d need whenever warmer weather finally returned.

Settlers and the Frozen Straits

Winter in the Straits wasn’t exactly forgiving. Winds off the lake could be brutal, and deep snow made even the simplest tasks a challenge. When the settlers arrived, they had to quickly learn survival skills that would allow them to thrive in the area.

Early colonial homes were built small, often with just one heated room surrounding a central hearth. Food storage in colonial times had to be just right to ensure winter survival. Early settlers used smokehouses, root cellars, and snow-packed meat caches to keep supplies from spoiling.

By the Victorian era, they were cutting huge blocks of ice from the lake, hauling them to shore with horse-drawn sleds, and packing them in ice houses with sawdust or straw. This ice kept food fresh year-round, crucial for preserving everything from dairy to meat. Most notably, it supported the local fish industry, allowing fresh catches to be stored and transported long after the wild ice had melted. Check out this video for a glimpse into what the ice harvest was like back in the day.

Travel across the frozen Straits of Mackinac was no joke before the Mackinac Bridge was completed in 1957. When winter came, the newcomers employed horse-drawn sleighs and early ice boats to haul people, mail, and supplies across the ice—when it was safe enough to try.

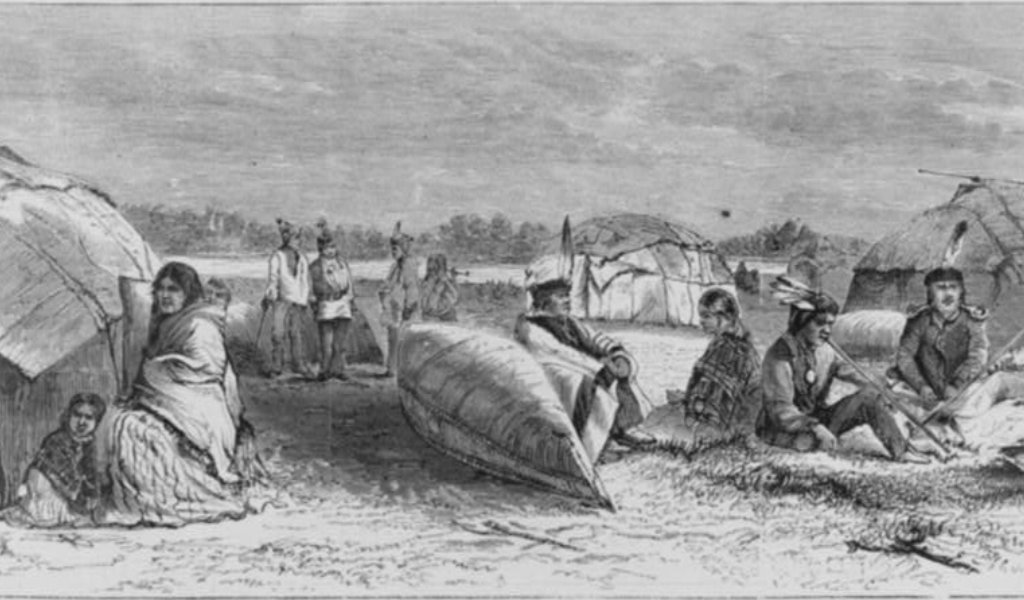

Icebreakers and the Lifeline of Winter Trade

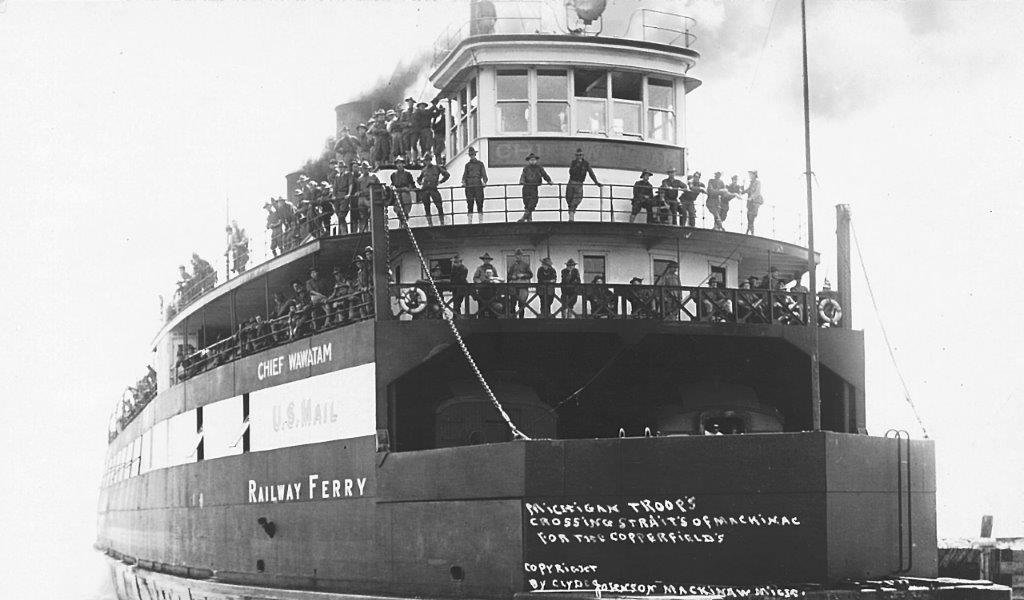

As the industrial age progressed, keeping goods moving between the peninsulas became a top priority, no matter how thick the ice. Enter the railroad ferries. They were giant rail-car transporting vessels that doubled as icebreakers.

The biggest of them all was the S.S. Chief Wawatam, a beast of a ship that could carry 26 rail cars at a time. For many decades, these ferries kept the Upper and Lower Peninsulas connected, even when the lakes froze.

From Past to Present

In the past, winter in St. Ignace could be a battle against the elements, but today, it’s an invitation to get outside! Visitors can walk those same trails once traveled by the Anishinaabe, or even cross the frozen Straits on the Mackinac Bridge in under a half an hour. The stories of the past winters live on, and St. Ignace welcomes you to add your own.

In winter, the Father Marquette National Memorial in Straits State Park is a great place to start! It’s open year-round, so you can walk or snowshoe the beautiful trails while reading about different aspects of the region’s past.

If you’re planning a summer trip to St. Ignace, you’ll want to check out the Museum of Ojibwa Culture. Located downtown, the museum is a good place to learn about the history, traditions, and stories of the Anishinaabe people.

For a taste of local heritage, the Annual Native American Festival on May 24, 2025, is a must-see that features drumming, dancing, workshops, and traditional foods.

And later in the summer, the St. Ignace Heritage Festival runs from August 8-9, 2025, celebrating the area’s history with live music, craft demonstrations, and great historical presentations.

Relax and Recharge: Book Your Stay in St. Ignace

As you explore St. Ignace’s interesting history, don’t forget to take time to enjoy all the area has to offer. After a day of discovery, relax at one of our accommodation choices, grab a bite at a local restaurant, or simply take in views of the Straits as the seasons change. Whether you’re here to learn, relax, or make memories, St. Ignace is the perfect place to experience it all!

Sign Up For Our Newsletter

Sign up for our newsletter and receive four seasonal editions.